Sitting in the Rynek Główny town square, the bustling sounds of horses hooves clattering along the cobblestones and the undulating waves of innumerable languages to keep me company, I reflect on the week behind me. Our journey began on an early Saturday morning where we hit the rode to Dresden fueled with coffee, chocolate croissants, and butter bretzels. A pile of rip-off Jordans took up too much space in the trunk and rolled around with turns and bumps. Tristan drifted between waking life and sleep in the front seat – earbuds firmly plugged into his ears; the volume turned up so loud I could hear the thwacking drumbeat over my audiobook. Somewhere along the journey, he moved to the back seat, and I was left feeling like I was vacationing alone. But then again, that often happens when you travel with a teenager.

Our arrival in Dresden was later than expected due to number of stau’s (stau = traffic jam) we ran into. So, we picked up our race documents, stopped for some carb loading, FaceTimed seester (Lacy), then crashed hard and fast at the hotel. I was eager to sleep through my nervousness for the race in the morning.

The alarm went off bright and early. Pre-workout chugged, last carb load devoured, electrolytes drunk, and after the thousandth pee, we lined up at the starting line of our very first 5k.

Tris and I bounced on our toes to stay warmed up; his hand occasionally grabbing my shoulder to make sure I wasn’t going to expel too much energy too soon, but then it was time to pound the pavement. Tristan darted ahead, setting his quick pace as he wove through the crowd of runners. I set my watch, started my music, and set my place amidst the rest – all of my nerves funneling into maintaining my form and 5.3 pace. Slow, yes. But steady.

Not even a km in, I noticed that I’d unintentionally set myself behind a small group of women running the same pace as myself, and an older gentleman walking with the enthusiasm of an Olympic speed walker. The entire time I was able to slow or quicken based on the distance I was behind them. I imagined myself as part of their team – mentally cheering them on as one foot slapped in front of the other.

Searching for the right 5k, my goal had been completion over fastest time. I wanted to see if I could do it – to see if I could run the entire thing without stopping, without giving up or bailing out. I wanted the accomplishment, the days and hours put into training my strength and endurance seen to fruition – to prove to myself that I was fully capable of more than I gave myself credit… I felt that sense of relief as I slowly made my way to the finish, the tears already burning in my eyes, the chill of the wind propelling me forward as I finally stepped outside of the pain – as I finally felt those coveted endorphins flood my body: the crowning achievement of my hard work! It felt phenomenal.

The following day, we packed up and headed east into a new adventure.

Krakow has sat at the top of my “to visit” list for quite some time, so I eagerly took advantage of our Easterly location in Germany to keep driving. It was another 5-ish hours on the road, but I pressed play on an audiobook and Tristan snoozed in the backseat again.

The city feels like coming home. It’s worn cobblestones and buildings giving it the sense that it has been well loved by it’s inhabitants… abused by its invaders – but standing tall, stubborn, and refusing defeat. I liked it.

navigate, easy to walk. There is no small selection of restaurants, stores, boutiques, and sites to visit. It made for lovely morning and evening walks to decompress from the day, especially the day after our arrival.

I’d booked a tour at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp the day after our arrival (I highly recommend booking a tour as far in advance as possible). This leg of our Spring Break trip already did not spring excitement in Tristan as he prefers shorter weekend or day trips, so when he learned of our tour to Auschwitz he further resisted.

Many who have known us for some time, know that I began Tristan’s Holocaust education very early, beginning with age-appropriate books, materials, and discussion. Of course, as he grew older, we adapted material that was more… uncomfortable. Establishing ourselves in Europe has given us an opportunity not many have to walk in the footsteps of history, good and bad. Taking advantage of this, we visited the Dachau KZ not too long after we arrived in Germany. For me, the walk through the buildings and grounds was a sobering, educational experience. For Tristan, is was visceral. After walking ahead through the first building, he ran out feeling like he was going to throw up.

He was nervous of duplicating this reaction, and so argued against the need to visit. Our discussion included a lot of “doing things that make us uncomfortable in order to learn” and “we must learn from the past by placing ourselves in the shoes of the oppressed, sacrificed, and abused.” I felt both firm and guilty in my decision; the importance of it too vast to waiver. I packed anti-emetics.

He declined them as we began our tour. Somehow I managed to book a personal tour, so it was just Tristan, myself, and our exceptional tour guide. He had personal stories of friends that had survived the camp. He took time to expand the full perspective of a space; to allow us to stand for a moment, absorbing the heaviness of what we were seeing, and settling into what we were feeling. He spoke directly to Tristan much of the time, holding his attention so utterly that at times I felt this tour was not for me. We felt lost in the absolute enormity of the camp and it’s extensions. We walked through the gas chambers where each tour group that walked in before us and after us did not utter a single word. The guides slowly and somberly ushered the visitors through, pointing over head to the showers of death. Stepping back into the sunshine seemed inappropriate and wrong.

Many in the different groups expressed tears as they were guided through the different buildings. Each contained exhibitions of what often occurred in them. Two buildings shielded the courtyard where prisoners were shot against the wall – bullet holes chipping the bricks in places. A memorial with flowers stood at the end of the narrow courtyard – we bowed our heads in silence and respect before moving into the next building. It was in one of these buildings where I encountered the moment I couldn’t hold back tears.

This building housed an exhibition of the “evidence of crimes.” It included piles of luggage, shoes, a tangle of glasses, prosthetic limbs and crutches, empty cans of Cyclon B, and other items that had been stolen from the imprisoned and murdered. Despair smudged its way up my throat from the pit of my stomach as we were introduced to the clothing and shoes from children taken straight from the train and into the gas chamber upon arrival. But it spilled over as we stepped into another room, turned to the right and stood before the display of the haircloth.

Our guide began to describe to us how the hair shaved from the heads of women was disinfected before it was packed into sacks and sold to German companies. Cloth, felt, rope, and other items were made from the hair of thousands. The bodies of murdered women were desecrated as their hair was shorn from their heads before they were burned to ashes or dumped into mass graves. He described the despair that many must have felt as their beautiful hair was stolen from their heads – and I lost it.

My hands reach up to the entangled, curly mass atop my head – I’d not washed it since running the race, instead refreshing with water and a hairdryer… but it had reached it’s limit of presentability, so I’d thrown it up, too lazy to wash it that morning. Yet, even in it’s current state, there was no doubt in my mind: I’d have been devastated. I could feel the hope of survival washing away with each imaginary strand that fell to the floor.

All I could say was, “My hair is my identity.”

Our guide nodded and spoke more on how this must have felt, but I could no longer truly hear him. It’s so much more than an identity – it’s an extension of me; of who I am. It’s an extension of my health, physical and mental. It’s a piece of my soul. And to have that ripped away from me without my consent – it being a decision I did not make – would utterly defeat me. My existence would be crushed. Obliterated. My will to survive gone in the mere moments it took to shear my soul. The theft would have symbolized the end for me.

In Indigenous American cultures, the hair is an extension of the body, legacy, and spirit. It is a link to the ancestors; carries memories and emotions. Cutting hair after the death of a loved one is performed by some tribes as a ritual of respect and mourning – a shedding of the memories and loss. But there is no shortage of cultures and religions that hold such reverence… such sacredness of ones hair.

And here – here in this place of mourning and memory and loss, I felt heavy and overwhelmed with the stolen identities.

We stood there for a moment in silence. I think our guide recognized the weight I felt; the time I needed to process what it would have been like; to imagine myself under the brutality as my curls were ripped from my skull and all hope diminished.

I took a deep breath, exhaling the sorrow, then we moved on to the next exhibition.

I now sit at home at the kitchen table. Many weeks have passed since standing in Birkenau, another installation of the massive concentration camp. My fingers can still recall the feel of the worn wood of the stacked bunks; my ears ringing with the disdain and anger of the tour guide as he pointed out the graffiti of the visitors. His voice was thick with an acceptance that humanity is lost; that people will continue to destroy other people as he pointed in the direction of not-so-far Ukraine. The memory of the infamous gate and railway into Birkenau is imprinted on me forever as I think about how lucky we live. All of the things my eyes gaze upon in my home are just things. Things I’ve collected along the way; money frivolously spent for comfort; the black leather chair that’s been sat in the rooms of countless members of my dad’s family. These “just things” have so much held in them, though. Some of these “just things” journeyed across the Atlantic, held me as I cried, watched me as I laughed, heard the yelling and fighting between Tristan and I. They’ve welcomed friends and family into their embrace, and sat waiting for our return home… our return to what is familiar – and in that, our comfort and safety.

My pride in Tristan also grew exponentially during our visit to Auschwitz. At the end of our tour, the guide immediately reached for Tristan’s hand. He grasped it with both of his and thanked him for his attention and respect. He thanked Tristan for allowing him to tell the stories that had been passed down to him; to educate him of the horrors of our past and lessons for our future. I gripped Tristan’s arm with affection and thanked our guide – his knowledge and time were priceless.

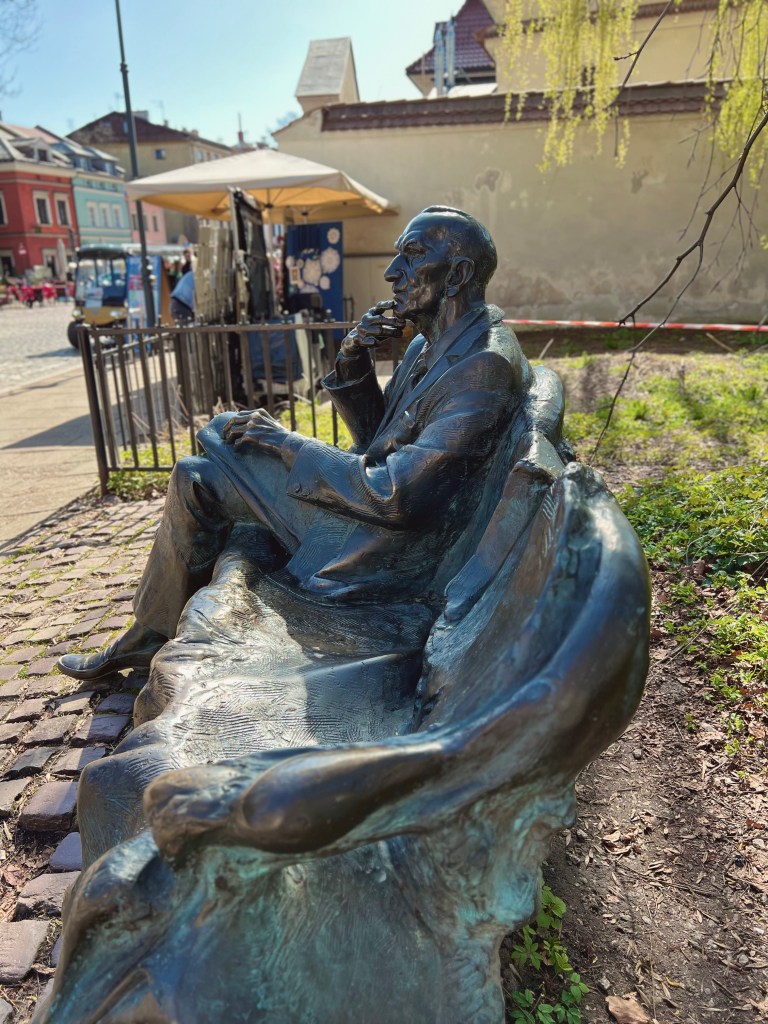

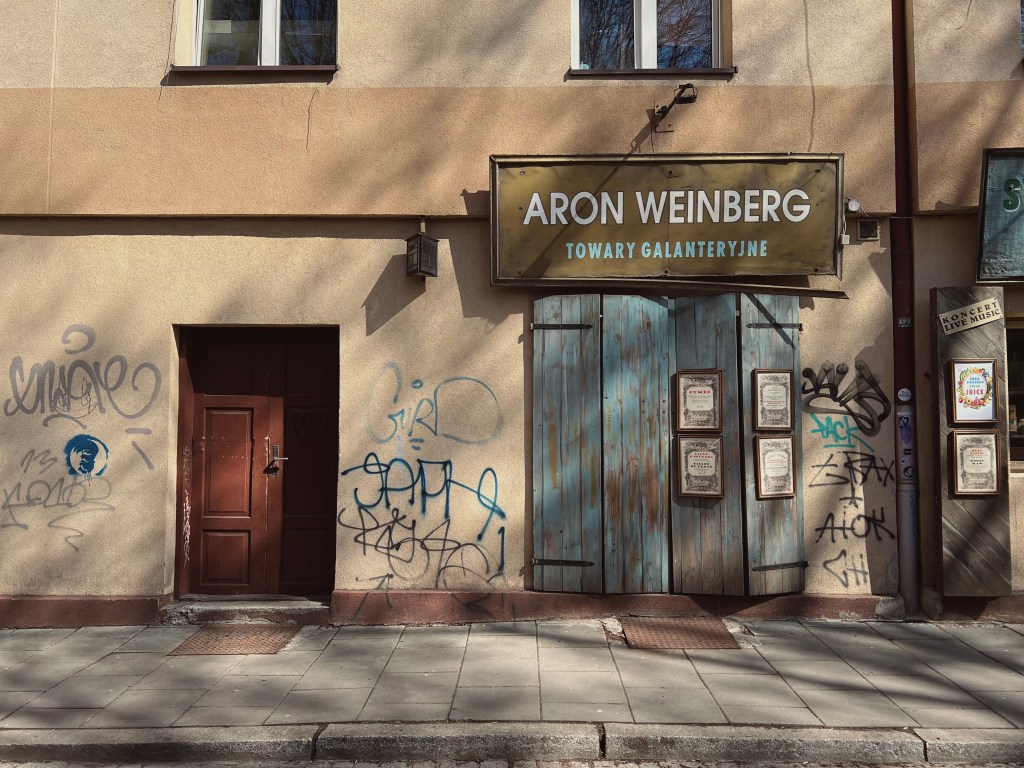

The rest of our time in Krakow was spent meandering the old streets separately. Tristan needed quite a bit of decompression time, and so I left him in our room to come and go as he pleased while I toured the Jewish Quarter. We ate our fill of Pierogi’s; I drank a cappuccino in a Harry Potter themed cafe that filled a basement space, the cloud of frankincense leaving me foggy for an hour or so; sat outside and people-watched; and wandered through the markets.

The day we left, we packed out early in the morning. We stopped for coffee and pastries, then drove by Schindler’s factory before we hit the highway for the long drive home. Spring Break was well spent.

Leave a comment